Climate change upside down: a look from Zimbabwe

The road from Vic Falls to Hwange is surprisingly well paved. “My taxi” is supposed to pic me up at 10:30 but, yeah, African time. At 11:20 we’re good to go. G. is coming with us. He is my sponsor here: he arranges things for me, knows plenty of people, speaks quite a bunch of local languages, has excellent tips on what to do and what NOT to do and he’s particularly good at getting rid of drunk local people annoying me a bit too much. His cousin F., in the front, looks like a local but I suspect he secretly comes from Jamaica. The playlist is an endless stream of dancehall local hits and he’s particularly keen on smoking a joint every twenty minutes. It reminds me of one of my former flatmates from Sardinia. He’s also quite funny. There also other two friends coming with us, or perhaps just random guys who figured why not take advantage of the ride. They’re nice and smiling too so I don’t mind.

It is a Sunday trip to the stadium in “nearby” Hwange to see a match. People here are just as crazy about football as are in Italy or Argentina. You wouldn’t have guessed it but they really don’t give a s**t about cricket or the like. They all sports Man City, Man United or Mbappé shirts (G. has one too). I would have guessed Mané too, but, hey, he is from Senegal, so maybe not a big Star here. That’s one of the reasons I felt like going. After all I was very curious to see a match of the Zimbabwean Premier League, that is the top ranked football championship in Zim. The local Premier League, as the name obviously implies. More like a broke, but really authentic, version, compared to the incredibly rich cousin.

The road to Hwange traverses an endless forest. Really, it is just basically trees for almost 100km. No cities, not even villages on the road. Just pure nothing. I can’t even manage to sleep. I should probably ask for a spliff from our friend but I am not keen on smoking. They even offer me a beer but it’s a bit too early for my taste so I decline the offer. Man, here people drink SO MUCH. Anyway the trip goes quite smoothly, one dancehall hit after another, all in local languages except for a very few (Sean Paul here and there), one joint after another. After a bit more than one hour we reach the suburbs of Hwange, or rather its industrial area. I told G. I wanted to see the coal mines but it was not quite possible (too bad, but I am probably happy with Potosì once and for all¹). So we’re going to see the processing plants, assuming the local guide shows up.

Natural resources in Zimbabwe

Hwange is sitting on one of the largest coal fields in Africa. It really is a treasure for Zimbabwe. Or it would have been two hundred years ago, as burning coal is not such a great idea as we’ve found out in the last decades. In spite of the poor state of its economy, Zim is fairly rich in natural resources. Diamonds, just like — if not potentially more than — neighboring South Africa and Botswana, but also gold, nickel, copper, iron ore, lithium and coal.

Given the mineral riches of Zimbabwe many might wonder why it is such a poor country, with a PPP (parity purchase power, that is, accounting for inflation) GDP, as of 2022, of about $41.3 billion dollars, about 118th in the world and PPP GDP per capita of $2530.6, 179th out of 196 countries²? The economical history of Zimbabwe and the causes of its present state are quite complicated and not the focus of my post, so I won’t delve into those here. One thing is for certain: resources do not guarantee development. Many economists call it the “resource curse” or the “poverty paradox”³, and there is a big debate as to whether it is real and to what extent, but one thing is guaranteed: you can make a lot of money exporting natural resources but that does not necessarily mean your citizens will become richer. An economy heavily dependent on exporting minerals, for instance, can be vulnerable to the change in prices of this resource if it does not invest in other activities and relies heavily on it. Institutions and politics matter quite a lot, as well as a stable government, absence of armed conflicts, ecc. Poverty is a complex phenomenon⁴.

The Coal Industry in Hwange

The air is dusty and the heat, in spite of the winter season, feels more pronounced here. Since the guide does not show up (it won’t come, in the end) we turn left and we approach the first gate. The guard in the booth does not seem to be too interested in us, and gestures us to go, while lifting up the gate. We can enter. After a few minutes of driving and a few trucks passing by we reach the first plant. The gate is open, a guard is sleeping in the booth and we can spot a few workers. I try to shoot a few pics from the back of the car. G. tells me that it is better not to get around and start shooting pics as not to upset anybody here.

We keep going through the processing plants, snaking through a dusty road. Trees aside the landscape is a bit desolate, its colors giving way to a persistent black hue, interspersed with the sandy yellow typical of this part of the plateau. We get to another checkpoint: a lady opens up the van to see who’s in and she’s quite shocked to see me. She hurries us away. My companions told me she’s probably afraid to speak to me in English. I just think she’s a bit surprised to see a white person here: a tourist? what for After all, all the non-Africans here are probably Chinese. The company owning the mines and the plants is local, the Hwange Colliery Company Ltd (HCCL, founded here in 1899), but in recent years there has been considerable Chinese investment in the area. HCCL also owns the stadium in Hwange, and perhaps plenty of other estate and property in the area. Hwange itself has grown from a little town to a city thanks to the coal industry. The Chinese have for sure brought lots of money and investments, but also plenty of controversy, environmental issues and resistance from locals (see https://cite.org.zw/hwange-community-sues-chinese-mining-company/ and https://thezambezitimes.co.zw/2021/02/26/xtractive-companies-continue-to-invade-hwange/). It is not a mystery that China is expanding throughout Africa and investing money as part of its Belt and Road Initiative, especially in the construction and mining sector, in exchange for natural resources. Zimbabwe makes no exception, although the share of Chinese investment here has steadily declined a bit in the last ten years or so⁵.

This fact has important geopolitical implications for the change of economical (and political) equilibria globally but also within Africa itself. What remains to be seen is whether these investments would actually improve the lives of people here or just become a new predatory system. Same stuff with a different face. After all, even the Brits built quite a few railways, no? But they had to shroud themselves in the hypocrisy of the “white man burden”; perhaps the Chinese can do without it.

Zimbabwe’s electricity and energy production

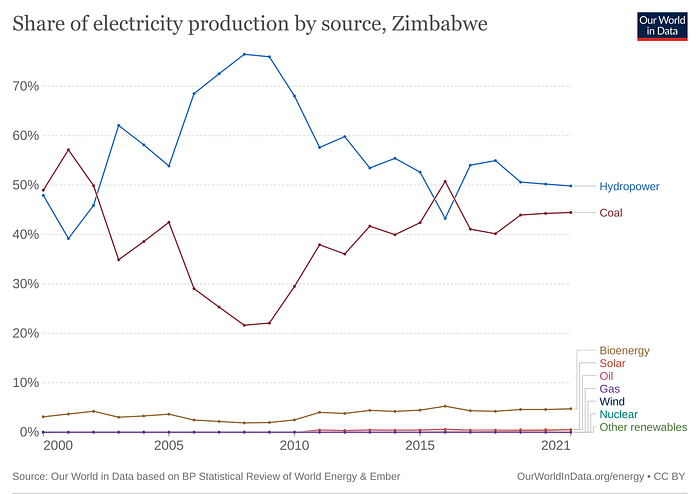

While we drive away from the plants we get to see the thermal (coal) power station of the city, that powers most of the north-west of the country, including Victoria Falls. Zimbabwe energy mix is really not that complex, and when it comes to electricity is quite simple: coal and hydroelectric.

If you look at the relative import of the different sources, however, we see a significant surprise: one hydroelectric power plant — the Kariba dam over the Zambesi river — provides roughly half of the country’s electricity (and it is shared with Zambia!). This is massive. This means that half of the country’s electricity comes from renewable sources, more than many other countries. You have to give credit to the Zambezi: it really carries a massive amount of water.

On our way to the city, trying to get a mouthful before lunch, the inevitable question arises: do you have coal in Italy? how do you get energy there? So, I find myself in the uncomfortable position of trying to explain why are phasing out coal to my Zim friends because it is bad for the environment and accelerates climate change, because of the CO2 emissions. I have to explain it to people who use coal as a large source of energy in their country and have no electric cars. How could you envisage a change that would bring clean energy here, to people who can barely make ends meet, and for whom coal represent such an important resource (both economically and energetically)? How can you tell them that in Europe we are transitioning (way too slowly!) towards different sources of energy and that they should cut their CO2 emissions?

Unlike what many people might think (including me till no long ago, out of sheer ignorance), South and Eastern Africa are doing fairly well in producing their energy from renewable resources (except for a few cases like Botswana, South Africa, Somalia and South Sudan). So I don’t think we have any moral high ground to preach pretty much anything about this really.

Still, since almost half of the country’s electricity comes from coal sources, there seems to be much room for improvement, no? Yes, they could cut their emissions too, sure, by producing less energy(!) or working on efficiency⁶, or by switching from coal to other power sources. But what if almost half of the country population has yet no access to electricity on a daily basis, should we just leave them in the dark?⁷ What if, even today, there are still major power cuts throughout the country⁸?

Electricity demand and CO2 reduction on a global scale

There are many reasons why we should give up coal and other non-renewable sources, climate change being the most obvious, most urgent and most crucial for our survival as a species. But looking at the whole perspective from the bottom up we can be sure of this: we are doing way too little, while they are doing what they can (and for some countries it is surprisingly well!). Why? Because we can afford to lose something (we swim in material abundance. Do we really need to change car every 3–4 years or buy a new smartphone every 2?). Here they can’t. And even if they could, from the size of their consumption — not just Zimbabwe, but for almost all of Africa! — , on a global scale, it does not seem it would matter much compared to other power-hungry countries. To make an example, in 2022 China consumes more than 8000 TWh, the US more than 4000 TWh, while Zimbabwe about 9.8 TWh. It is more than 100 times less. It seems like we shouldn’t really be having this conversation in the first place.

Perhaps we need to compensate for their emissions too, provided that they can transition energetically at a later stage, after they got enough on their plate to even care. After all, we have a head-start of a couple of centuries, don’t we?

- In 2013 I managed to infiltrate — not really, it was a guided tour , but it sounds cooler this way — a cooperative of miners in Potosì, Bolivia. They mined in cerro rico, the rich mountain, possibly the largest silver mine in the world (at least it has been for centuries, supplying endless silver to the Spaniards). It’s been an incredibly authentic — and frankly, a bit dangerous too — experience. It’s there I realized that: a) you can buy dynamite without any sort of licence in Potosì; b) mines are REALLY hot and c) safety is hard to come by when you are poor and scraping for a few grams of silver.

- see the World Bank data for 2022 (https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/NY.GDP.PCAP.CD?locations=ZW&most_recent_value_desc=false)

- The term resource curse was first used by economist Richard Auty in 1993 (“Economic Development and the Resource Curse Thesis”) and made famous by a 1995 paper authored by Jeffery Sachs and Andrew Warner titled “Natural resource abundance and economic growth”.

- An excellent book to understand how poverty works and why it can be so hard to fight is https://economics.mit.edu/people/faculty/abhijit-banerjee/poor-economics.

- For a more comprehensive study of Chinese foreign and direct investment in Africa see https://www.cgs-bonn.de/cms/wp-content/uploads/2022/07/CGS-China_Africa_Study-2022.pdf

- Looking at the data there seems to be room for improvement. Zimbabwe’s economy seems to be pretty energy-intensive. This is probably owed to many factors, like technology and organization of labor. While there is room for improvement, it is worth noticing how — given the size of Zimbabwean’s economy — this should not be a concern for now.

7. Rhetorical questions aside, making sure that everyone gets access to electricity in this country is a top priority, but this also entails, all things equal, that more — likely coal — power plant will be built.

8. The day I arrived in Harare, the capital, there was a power cut that lasted from 4pm till… the next day I left early so don’t really know. It was probably confined to our block, but still…